Tariff Tantrum

The fallout from “Liberation Day” has been anything but liberating! The Trump Administration managed to thoroughly upset global markets with the rollout of “reciprocal” tariffs. Following the initial release on April 2, markets began a sell-off which increased in intensity throughout the remainder of the week. Thursday, April 3, was the worst one-day decline in the S&P 500 since the Covid pandemic induced a bear market in March 2020. The subsequent drop on Friday, April 4, moved this S&P decline to levels rarely seen since the 1987 Black Monday crash. Additionally, the drop on Friday witnessed the VIX Index rising to over 45 before closing a bit above 44 as the trading day ended. The drop coupled with the corresponding volatility levels are relatively rare from a market perspective.

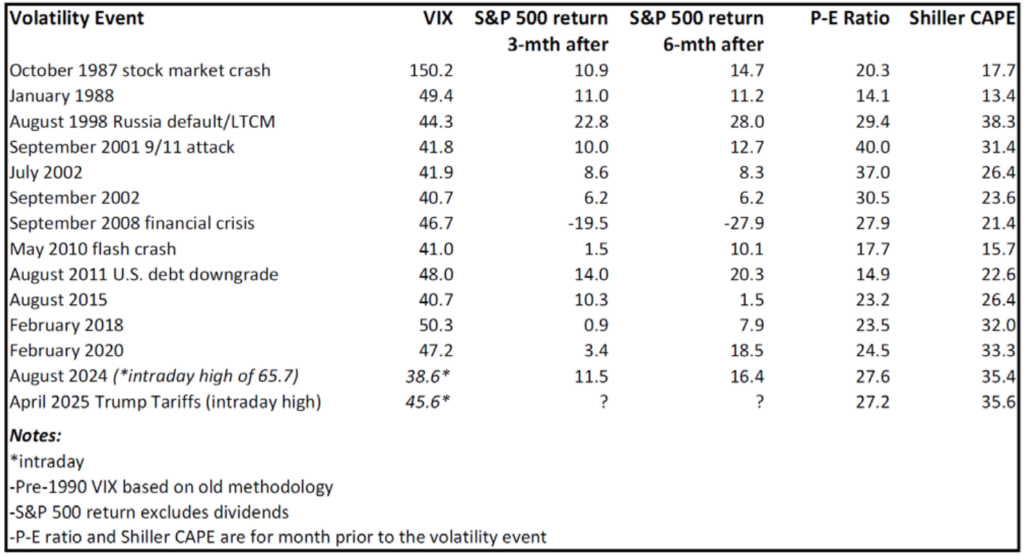

As our friends at RDQ pointed out, such declines and corresponding volatility levels have occurred with similarly momentous events like Covid, the Great Recession, 9/11, LTCM, etc. The firm provided the following table outlining these major decline events:

As is so often the case, RDQ’s thoughtful analysis suggests that overreacting to these extreme events is seldom wise. That, of course, is our view as well, but nonetheless we have been receiving questions about the tariffs and our expectations for the economy and markets.

Given the uniqueness of this event and the extremity of the market reaction, we wanted to send a short update prior to our normal quarterly commentary sharing a few thoughts about the current environment in general and the tariffs in particular.

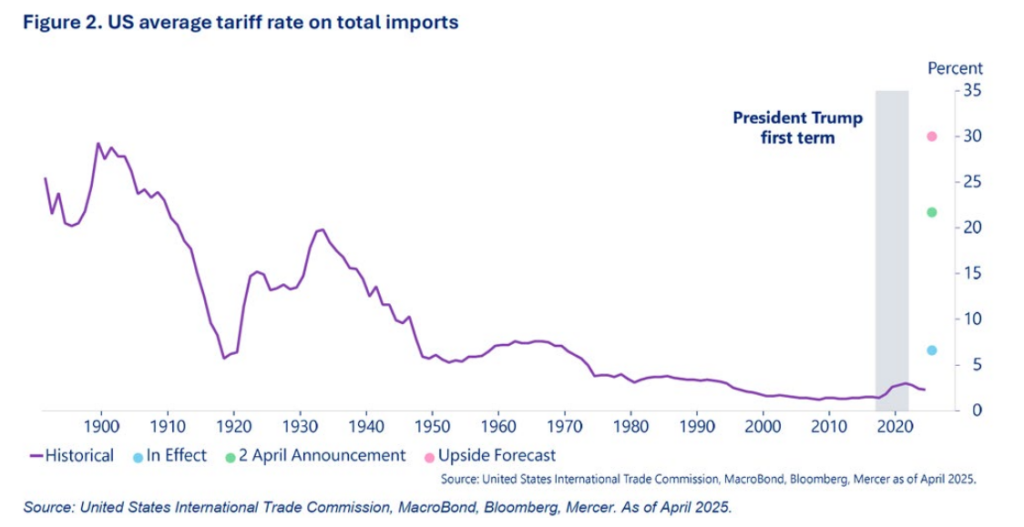

There seems to be little question that this round of tariffs is the most aggressive put in place by the United States since the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act in 1930. Many of us remember little about that time period other than being taught that tariffs were bad and the Smoot-Hawley Tariff was thought to contribute to the pain of the Great Depression. What is not discussed as frequently is that prior to the U.S. implementing a federal income tax, a significant amount of our national income came from tariffs. However, following the massive decline in global trade brought about by the Smoot-Hawley Tariff, the benefit of such an aggressive tariff regime was questioned. As economists continued to develop an economic framework around a nation’s “competitive advantage,” a growing doctrine around the benefits of free trade was formed. Throughout the next 75-80 years we were taught that free trade and the maximization of one’s competitive rather than absolute trade advantage was a “free lunch” allowing all participants to benefit. Various organizations like the World Trade Organization (WTO) and its predecessors propagated and supported this system. However, in recent years there has been growing discontent surrounding these practices. This discontent has largely centered around the belief that the U.S. has often been too accommodating and has allowed other nations to take advantage of its open trade policy.

Conceptually at least, many of us might agree that there is some truth in this allegation. The U.S. has generally pursued an “open trade” policy for the last 35 years, and the policy, along with our expansive foreign aid packages, has benefited the world at large. I would argue that this policy has benefited the U.S. as well, but that perhaps with the addition of China into the WTO in 2001, the balance began to shift. Few would deny that China has taken advantage of its status and has grown its economy and tech stack at the expense of the Western World in general and the U.S. in particular. As fears have grown around Chinese ascendency and the potential for a bipolar balance of power challenging U.S. hegemony, the pressure on international trade and on current regimes has grown.

The Trump Administration has vowed to take on these imbalances and has highlighted tariffs as a significant element of its trade policy to accomplish this objective. However, it is important to note that as Wall Street and Main Street sought to determine exactly what this “rebalancing of the playing field” would look like, significant concerns have arisen. Initially, many including Cornerstone expected Trump’s team to utilize tariffs primarily as a negotiating tool to extract better trade terms from “bad actors” around the globe and to secure for the U.S. a more favorable position in various markets. Taking it a bit further, I believe many also hoped Trump’s plan would support the positive elements of “re-shoring” and “near shoring” which arose out of the supply chain debacles of Covid. Perhaps some even envisioned protections for strategic industries. However, few observers expected the administration to put in place the dramatic tariffs announced on April 2. In fact, most research teams had modeled out a “worst case” expectation of 10% across-the-board tariffs; instead, those announced exceeded 20% on average.

As Mercer illustrates in the graph above, the tariffs announced on Wednesday, April 2, massively exceeded the expectations of both Wall Street and Main Street. We believe the combination of the scale of the tariffs coupled with the “surprise” factor contributed to the significant market decline at the end of that week.

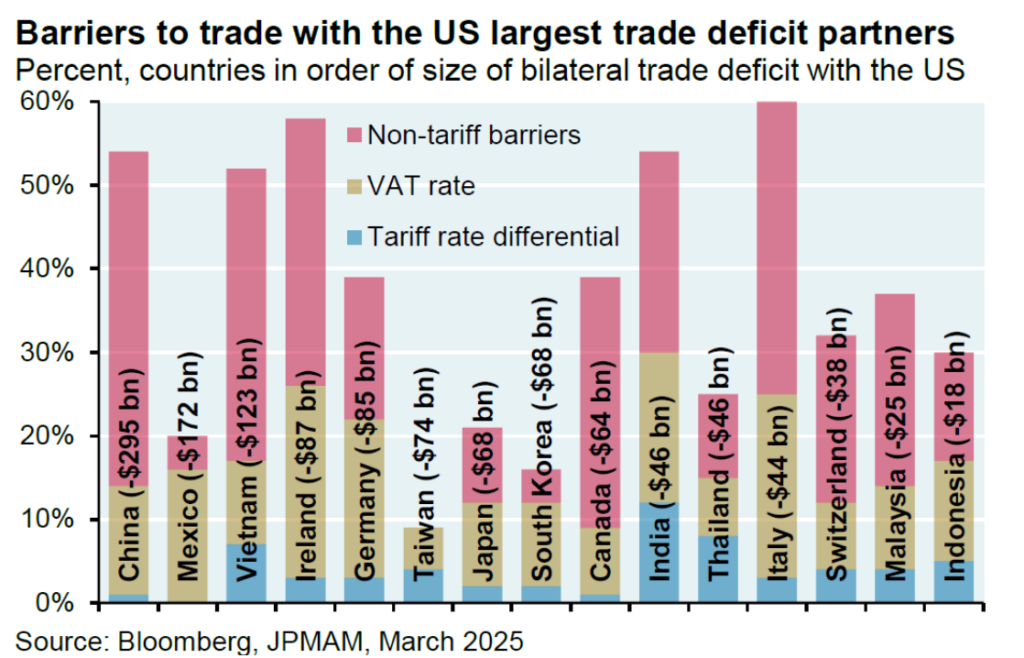

The market has been somewhat negative as tariff fears have grown and has declined from its near-term peak in February, but this last wave of selling is quite different. In our view, it represents investors coming to grips, perhaps for the first time, with the full scope of the administration’s plans related to global trade and the U.S. economy. As we mentioned earlier, tariffs are not the only method of restricting or limiting imports from another country. Rather, there are various barriers that countries can put in place to limit trade. As Michael Cembalest pointed out in one of his recent missives, these other barriers to trade really do matter.

(Cembalest also noted that adding the “VAT” (Value Added Tax) component really didn’t make any sense to him!) The administration had indicated it would take these other factors into account as it structured the tariffs. However, as the data was released and subsequently reviewed, it seems that the most significant element in the calculation was simply the bilateral trade balance between a particular country and the U.S. What has really rattled many economists, consultants, and observers is the fact that it seems the administration is bent on seriously limiting or eliminating the U.S.’s bilateral trade deficits with various countries rather than simply “leveling the playing field.” Further, in some cases where the U.S. actually had a trade surplus, a minimum tariff of 10% went into place anyway.

A key additional element that we must explain at this juncture is the U.S. capital account and the dollar’s status as a reserve currency. If the U.S. runs a trade deficit, which it has done for many years, then it imports more than it exports. In this way more dollars leave the U.S. and move into the hands of foreign investors who can then invest those dollars back into the U.S. If this wasn’t the case, then the subsequent demand for dollars by foreign investors would put significant upward pressure on the dollar. Further, it could cause the dollar to lose its “global reserve” status. It is that very status which has allowed the U.S. to borrow with impunity, cheaply finance its growth, and some would argue bolster the knowledge economy. Trade deficits or surpluses are not necessarily intrinsically bad or good. The challenge in the case of the U.S. is that our economy has shifted. That shift, perhaps, is where we are both empathetic toward Mr. Trump’s position, but also somewhat opposed to his objectives.

The U.S. has been on the road toward becoming a knowledge economy for many years, and we do not agree that the answer to all of our problems is to try to recreate the U.S. as an industrial powerhouse. From an economic security perspective, there are certainly elements of the industrial base which we cannot afford to lose and that we must work to protect, but a wholesale transition is in our view both unwise and unattainable. Regardless of whether one agrees with the administration or not, these tariffs were significantly more aggressive than expected and have dramatically impacted the market. If the majority of them remain in place, they will undoubtedly impact the economy and corporate profits as well.

In our view, the situation is fluid and much could still change. However, we also believe the probability of a more negative short-term outcome has risen dramatically. We have yet to talk about the Federal Reserve or other economic data including inflation. Whether one believes that tariffs lead to longer term inflationary pressure, it is generally accepted that there will be some immediate impact. To better understand the impact of a tariff, it helps to remember who might pay the cost of a 20% increase in the price of a good. Much of this depends on the elasticity of demand, but let us assume for a moment that a particular good has a relatively elastic demand curve and that switching goods is possible – say, a Tesla for a Mercedes. The foreign exporter could lower the cost of the good in dollar terms and thereby take the hit…this is what Mr. Trump often highlights as the optimal outcome. We must remember that there is not always a lot of incentive for that exporter to the U.S. to absorb the margin hit. Perhaps the exporter simply ships the Mercedes to another country. Another outcome is the importer of a particular good absorbing the cost. We might see this in the case of Apple with a part for an iPhone. Apple simply absorbs the additional cost and lowers its corresponding profit margin. In this case we have essentially raised the corporate tax burden on our own U.S. companies without raising the corporate tax rate. Finally, the good can simply go up in price to accommodate the tariff, meaning the end consumer pays the price in the form of price inflation. In each of these scenarios, the tariff acts as a tax.

In most cases economists believe that the first order price adjustment is relatively quick and, in this case, significant, but the knock-on effects are difficult to assess. Most of the economic estimates we have seen following Trump’s April 2 announcement suggest a potential hit to U.S. GDP on the order of 2% on an annualized basis. We have already seen a significant impact to GDP during the first quarter as firms sought to get ahead of the tariffs. There was also a unique issue with gold imports during the first quarter which further exacerbated this challenge. Consequently, we likely experienced flat or negative GDP growth during the first quarter of 2025.

If the current tariff regime is kept in place over the next several weeks without significant revision, it is quite likely that second quarter 2025 GDP growth will be negatively affected. This could lead to the U.S. entering at least a “technical” recession. Just a few weeks ago, this seemed highly unlikely, but with the latest data the odds of a recession have significantly increased. Additionally, corporate earnings are likely to be negatively impacted at a time when equity prices are high. Unfortunately, as we noted, tariffs can also lead to additional inflationary pressure, much like the supply shock brought about by Covid. Consequently, the Federal Reserve may be forced to remain on hold. The fixed income market is already adjusting and is now pricing in one to two additional rate cuts, but the Fed is pushing back on that narrative. In our view it would be naïve, at this juncture, to look to the Fed to bail out equity markets.

So, what should we expect? In short, additional volatility. There is hope that many countries will negotiate quickly and corresponding tariff rates will be revised. If this were to happen, the U.S. could avoid recession. Without that quick response it is unlikely the U.S. can avoid a recession. The ISM Manufacturing Index dropped back below 50, and the ISM Non-Manufacturing Index is hovering just above 50. Unemployment is hanging in around 4.2%, but small business sentiment has declined rapidly and CEOs are becoming more cautious.